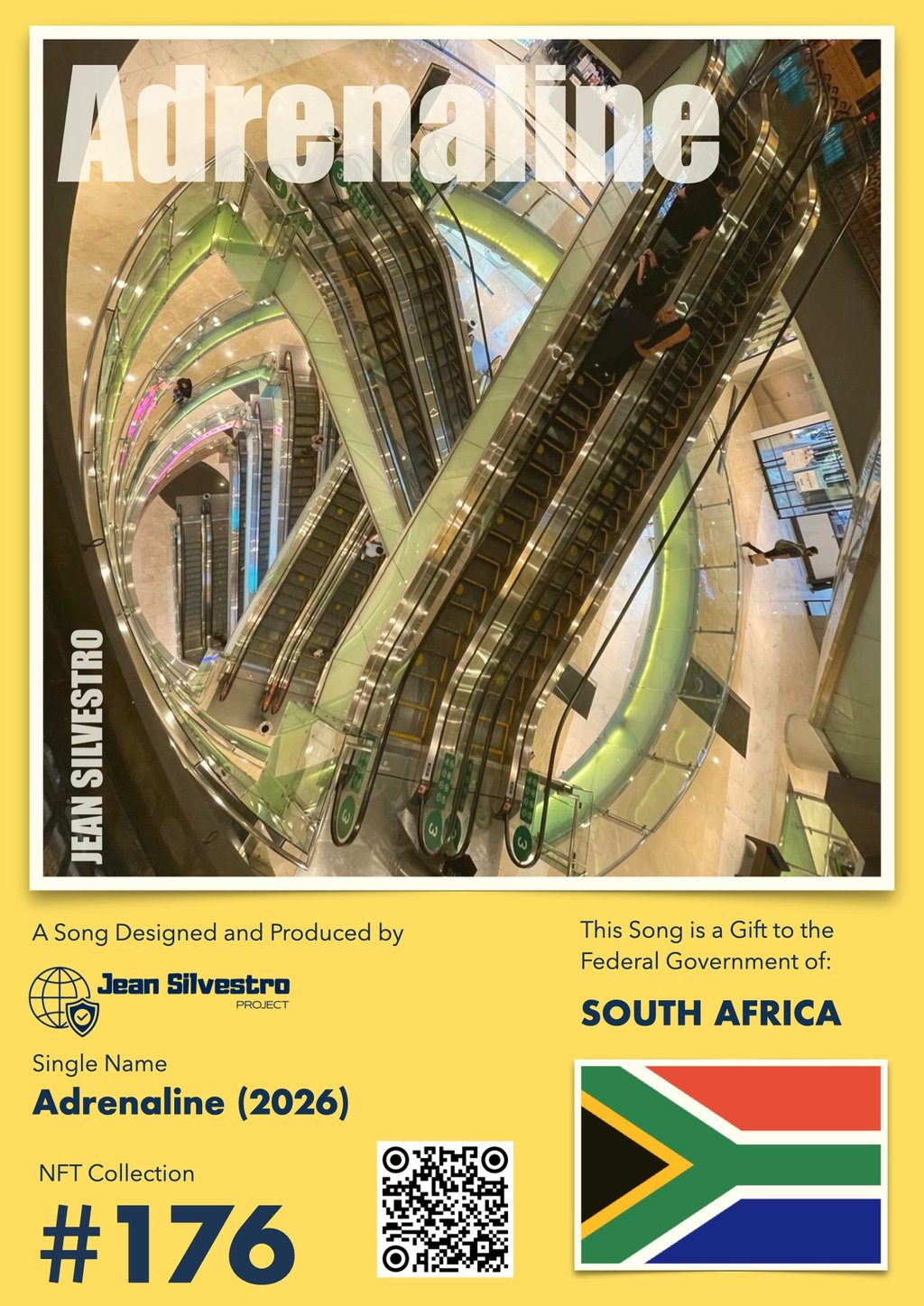

#176 Adrenaline (2026)

Lyrics

What really separates us

From now and yesterday

Never hurts or makes me be afraid

It’s like a glass that never is gonna be broken

Eternal feelings... we will live forever

Now you can draw and paint

With divine brightness

And this vibe will make you live again

You can live

You can die

You can live and die again

You can live

You can die

We’ve got the infinity in our hands

Now you can touch the rainbow

Like you never did

Living your life infinitely

There’s no pain and sorrow...

I feel there is no change

Living and Dying it’s always the same

We will play this song

In the night

I believe you will never leave this place

You can live

You can die

You can live and die again

You can live

You can die

We’ve got the infinity in our hands

So anyway we’re gonna leave

And travel ... travel in peace

The universe forever

Every time we listen to this song

And travel ... travel in peace

The universe forever

We can live

You can die

We can live and die again

We can live

You can die

We’ve got the infinity in our hands

The Secret and Inspiration

What truly separates yesterday from today? I've been asking myself that question ever since that early morning in São Paulo. Yesterday, Ruy was laughing on my makeshift mat in the garage, talking about a new guitar he wanted to buy. Today he's just a memory. And the city keeps rushing by as if nothing happened. Sometimes it feels like there's an invisible glass between what was and what is—a glass that shouldn't break, but that violence insists on shattering.

I knew Ruy before everyone else knew the artist. Before the newspaper covers, before the tributes on social media. To me, he was just the guy with long, straight black hair, always tied back, a soft voice, a gaze too calm for the jungle that is São Paulo. Me, a jiu-jitsu fighter, used to training defense, discipline, and reaction. Him, a heavy metal guitarist, a talented tattoo artist, a visual artist who spent days painting giant floats for Carnival. While I released energy on the mat, he spread calm throughout the world.

We used to hang out in groups. Jean, Caio, Bruno, Renata, Andreia, Camila. Late nights on Augusta Street, beer spilling onto the table, loud music. Jean sometimes went overboard, laughed loudly, talked about projects, daydreamed. Ruy stuck to soda. Always soda. I never saw him raise his voice. I never saw him lose his composure. He observed, smiled, sometimes made a sharp comment that silenced everyone. It was as if he had found a different frequency than ours.

I have a tattoo he did on my right arm. Jean has another one on his body too. His hand was firm, but light. He drew like someone meditating. His studio smelled of ink, coffee, and weak incense. The walls were covered with his own artwork and photos of guitars. Sometimes, after closing the studio, he would pick up his guitar and play heavy riffs with an absurd serenity. Heavy metal coming from a guy who looked like a monk.

That February, he was working in a samba school's warehouse in the North Zone. It was the peak of preparations for Carnival. Giant floats, styrofoam, paint, iron, welding, sweat. He loved it. He said it was popular art on a monumental scale. While the city discussed football, politics, and crisis, he was there, painting colors that would shine on the avenue.

São Paulo has this nervous energy. Organized fan groups, old rivalries, people armed for nothing. That night turned into chaos too quickly. I didn't see it, I don't want to imagine every detail. I only know that a rival group invaded the warehouse. Shouts. Running. And in the middle of all that, Ruy—who was there only to work, only to create beauty—was hit. A shot. A mistake. An absurdity.

When the news arrived, nobody believed it. It didn't fit. It didn't add up. How could someone who emanated peace by his mere presence die in a fight that wasn't even his? The TV showed aerial images of the warehouse, reporters talking about urban violence, organized fan groups, crime. But no camera captured who he really was. No headline could explain the gentleness of his voice.

At the wake, Jean remained silent for what seemed like an eternity. Caio wept without trying to hide it. Renata held Andreia's hand. I looked at the body there and thought about the amount of energy that still existed in the memories. It seemed impossible that that calm had been interrupted by something so brutal. The body there didn't match his story.

Since then, every time I hear a distorted guitar, I remember his tranquil smile. Every time I look at the tattoo on my arm, I feel as if the glass was never truly broken. The city remains chaotic. The violence remains absurd. But there is something they couldn't take away.

You can live. You can die. But some presences don't end in the body. We carry infinity in our hands when we speak his name, when we play the songs he loved, when we tell stories of the early mornings in greater São Paulo. Ruy's body fell that night. But his vibration—gentle, firm, eternal—still travels with us. Travel in peace, my brother.

India - Performance

Each country profile presents the most recent data available on a range of indicators relating to the well-being of women and children. Each country profile page is composed of data from multiple sources, depending on the indicator domain. For example, child mortality rates come from the most recent data produced by the UNICEF-led Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation (IGME).

SDG indicators related to children

The 2030 Agenda includes 17 Global Goals addressing the social, economic and environmental dimensions of sustainable development. Attached to the Goals are 169 concrete targets measured by 232 specific indicators.

To map and monitor how ambitious and realistic countries’ targets are, UNICEF has created quantifiable country-level benchmarks for child-related indicators for which data are available to measure and monitor child rights on a common scale.

Below is a snapshot of the country’s performance against the 45 child-related SDG indicators, grouping results into five areas of child well-being to provide an overall assessment of how children are doing. Countries are assessed using global and national targets. The analysis provides valuable insights into both historical progress—recognizing the results delivered by countries in the recent past—and how much additional effort may be needed to achieve the child-related SDG targets. This approach provides a framework for assessing ambition as well as the scale of action needed to achieve it.

Jean Silvestro Project • 2025 • All Rights Reserved

The project is currently in the institutional consolidation phase, with legal and structural developments underway.